Jun 03, 2016 • 6 min read

The ACL Epidemic in Sports, Part 2: Who’s at Risk?

Click here to read part 1 of The ACL Epidemic in Sports.

Last week, you were introduced to TJ, a high school football player whose sophomore season was ended by an ACL injury. His story continues this week as he describes his unfamiliarity with ACL injuries and the factors that place many young athletes at risk.

“Until I tore mine, I didn’t really know what an ACL was.”

TJ explains that after he was diagnosed with a complete ACL tear, he and his parents had many questions about what had actually happened to him. Being the first player on his young coach’s roster to have an ACL injury, TJ and his family turned to the school’s athletic trainer for answers. “My athletic trainer taught me and my parents all about my ACL injury during my recovery.”

TJ explains that after he was diagnosed with a complete ACL tear, he and his parents had many questions about what had actually happened to him. Being the first player on his young coach’s roster to have an ACL injury, TJ and his family turned to the school’s athletic trainer for answers. “My athletic trainer taught me and my parents all about my ACL injury during my recovery.”

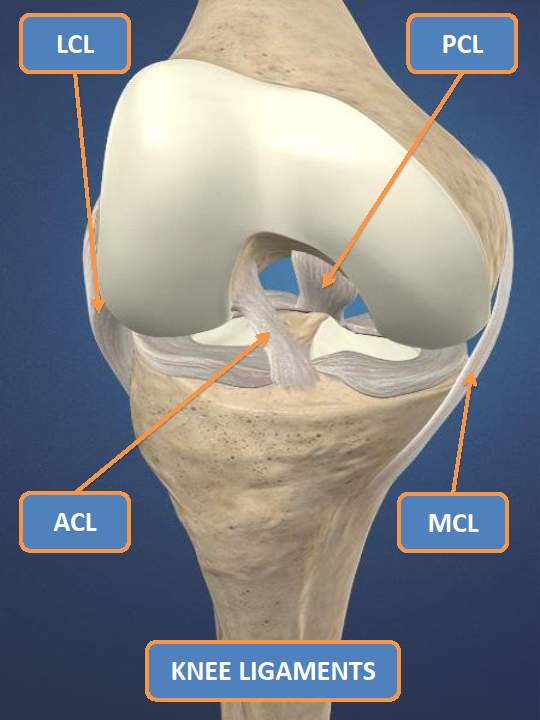

Unfortunately, parents and coaches of young athletes like TJ are learning about ACL injuries all too often these days. And most often the ACL, or anterior cruciate ligament, is one of the four main ligaments in the knee. As seen in the picture to the left, the ACL is situated near the front of the knee where it helps to provide support for the joint. The ACL can tear when an athlete collides with another player or object (contact injury) or more commonly, when the forces produced by an athletes’ movement are greater than the ACL can withstand (non-contact injury).

There are many factors that predispose young athletes to ACL injuries. Most of these are directly related to the athletes themselves, or intrinsic factors which include:

Neuromuscular Factors

Differences in strength, balance, coordination, flexibility and agility allow athletes to perform athletic activities and movements in their own unique way. Imbalances or deficits can cause an athlete to move in a way that places excessive force and strain on the ACL, greatly increasing the risk of tearing the ligament. Activities such as jumping and landing, changing direction and changing speed with inadequate neuromuscular control have been found to cause many non-contact ACL injuries.

Gender

Female athletes have a higher risk of injuring their ACL, with injury rates more than two times greater in soccer players and more than three times higher in basketball players. Males and females often move differently when changing speed, changing direction and jumping and landing, putting females at greater risk of injury than their male counterparts.

Previous Injury

Nearly 25% of athletes who’ve had an ACL injury will experience another ACL injury in either the same knee or the opposite knee. Athletes with an ACL injury in the previous year are over 11 times more likely to suffer another injuries compared to those who were uninjured.

Fatigue and Dehydration

Fatigued athletes often experience changes in strength and body posture over the course of a practice or game. Being tired changes the way an athlete moves and increases the risk of an injury.

Dehydration impairs neuromuscular control and balance and raises the risk of injury. Dehydrated athletes have more unwanted hip, knee and ankle movements and sway more when standing on one leg when compared to athletes that are well hydrated.

Others elements that contribute to ACL injury risk are associated with outside or extrinsic factors, including:

Playing Surface

Athletes who play on synthetic indoor surfaces are more than twice as likely to experience an ACL injury as those that play on wooden surfaces. Researchers have also found that the rate of ACL injury among college football players on artificial outdoor turf is almost 1.5 times greater than the injury rate on natural grass surfaces.

Shoe-Surface Interface

Too much or too little friction between the ground and an athlete’s shoes can alter his or her ability to maintain a stable contact point. For example, wet surfaces decrease the amount of friction and can lead to an unexpected fall or loss of balance.

ACL injuries have also been linked to athletic shoes with long cleats on the outside borders of the shoe and shorter cleats in the middle. This design creates higher levels of turning force than shoes with shorter or fewer cleats.

While some of these factors, such as gender and playing surfaces, cannot be changed, it is crucial that those responsible for the safety of young athletes be aware of those factors that can be changed. TJ’s athletic trainer was instrumental in identifying the issues and developing a plan to correct these factors after he was injured.

“Since I already had an ACL injury, I had to be fully prepared before I could play again,” TJ explains. “I learned about proper rest and hydration and how to run and cut the right way so that I was less likely to be injured once I returned.”

But raising awareness of risk factors and learning how to modify them isn’t only for athletes and shouldn’t only happen once a player is injured. It is a process that must also include parents, coaches and sports administrators. And it should be happening before athletes are injured, not after.

Part three of this series will take a closer look at why more than a quarter of a million athletes continue to have their seasons ended by ACL injuries each year. In the meantime, please share your stories of young athletes like TJ that have suffered an ACL injury and the challenges they have faced as a result.

The Sports Injury Prevention Program at Hospital for Special Surgery encourages parents, coaches, athletes, sports administrators, teachers and others that are involved in the development or training of young athletes to follow this series to learn how we plan to reduce the number of ACL injuries in young athletes.

Joseph Janosky is a Physical Therapist and Athletic Trainer and the Manager of the Sports Injury Prevention Program at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York. He brings more than 20 years of experience to the development of sports injury prevention systems. He has had considerable clinical involvement with youth, high school, collegiate, and professional athletes and among his many professional interests are ACL rehabilitation, care for the overhead athlete, motor learning strategies for sport skill acquisition, and preparing athletes for return to play after an injury. He has taught at both the University of Scranton and Marywood University and is currently pursing doctorate degrees in both physical therapy and human and sport performance.